By Uncle Dave Lewis

Wes Montgomery’s A Day in the Life is an album that has figured prominently in my life at certain points; tracks from it at first, and the whole album later. It participated in the background of my childhood, and as an adult I’ve tried to stay in touch with it. The vast majority of my record collection disappeared some years ago thanks to the deceptive and unscrupulous machinations of the manager of a storage facility, and since then I have slowly been rebuilding what I can of essential things that I must have. Over the weekend I found my third, and hopefully last, LP copy of A Day in the Life at the Northside Record Fair. Listening to it again brings along thoughts that I’d like to share here.

Wes Montgomery (1923-1968) and his brothers Monk and Buddy are related to my main research area, as they were major movers in the Indianapolis jazz scene of the 1950s. Some of the records which emerged from that scene were pressed in Cincinnati, though the only recording that the Montgomerys made in their hometown, The Montgomery Brothers and Five Others, came out on World Pacific, a west coast imprint (PJ-1240). Montgomery developed a signature style on the electric guitar based out of his contact with Charlie Christian’s records of the early 1940s; though his octaves – difficult to execute, by the way; I’ve tried – constitute the most frequently cited technique associated with him, Montgomery’s sound incorporates a lot of different figures; flamenco-like flailing, bluesy gestures and scales running up and down, etc. I read mention of his use of block chording, but actually I don’t note as much of that in listening to him; perhaps I’m missing it or my ears are on wrong. The prevailing attitude among many jazz critics in regard to Wes Montgomery is that his 1959-63 Riverside recordings carry forward the best of his efforts, and that afterward he gradually became mired into a pop context that sapped his creativity and spoiled his potential as an artist.

You know, I haven’t any idea what they’re talking about, and genuinely wonder if these folks are listening to the same album that I am. For me, every note of A Day in the Life is jazz, though my former colleague Scott Yanow at allmusic.com writes that, in this case, “the jazz content is almost nil.” That comment, for an album which uses a consistent backline of Herbie Hancock, Ron Carter and Grady Tate? This was the first of three LPs that Wes Montgomery made for A&M, a label that genuinely cared about jazz and sought to market it to a broader audience base than labels which regarded jazz as a cottage industry. Two of my favorite jazz albums of the 1970s – Charlie Haden’s The Golden Number and Don Cherry’s Brown Rice — first appeared, at least to me, on A&M. I like the pop albums that A&M made in the 1960s and very much appreciate the stab they made at incorporating punk and new wave into their stable around 1980. However, for me A Day in the Life is not a pop album, but jazz which incorporates extended language and notions of genre; if you want to find examples of that elsewhere in jazz, look no further than the 1920s, when jazz bands freely incorporated material from classical, opera and folk music into their mix. What I consider to be the first “free jazz” solo is a whimsical chorus played all rhythm, with no coherent ‘notes,’ by Louis Armstrong on “Go Long Mule,” a country song popularized by Jones and Hare and heard during the Scopes ‘Monkey Trial’ – hardly a jazz standard. It starts at 1:47

I guess that some of these jazz writers are thinking “string section equals no jazz interest,” even though Charlie Parker with Strings is one of the most revered jazz albums, and Chet Baker, Miles Davis, Artie Shaw and Glenn Miller all got a lot of mileage out of bringing string sections into jazz with success. Also, Montgomery’s transition to A&M in particular is seen as his moving from the pop frying pan into hell fire in comparison to his previous period with Verve. Discographies really put the lie to this; they show that Montgomery’s contract was simply taken over as is, and that he worked for A&M with exactly the same resources he had at Verve – same arranger (Don Sebesky), same producer (Creed Taylor), same studio and engineer (Rudy Van Gelder). One 1960s album I simply cannot listen to is Sebesky’s first solo outing, for Verve, Don Sebesky and the Jazz-Rock Syndrome – I think that was the first time the term “Jazz-Rock” was ever used for anything. But I do think Sebesky’s arrangements for Wes Montgomery are on point; I love the section in “A Day in the Life” (the track) that follows Montgomery playing the equivalent to The Beatles’ “… and somebody spoke and I went into a dream …” It reminds me of Christmas at shopping malls when I was a kid, where that very piece was heard over loudspeakers as my family made our way through the assembled multitudes. The weird, psychedelic section at the end of [Montgomery’s] “A Day in the Life” always transformed my Christmas surroundings into a surreal wonderland, which I loved, though it was always a little scary.

One of the authors of Montgomery’s Wiki writes of the A&M albums that “these records were the most commercially successful of his career, but featured the least jazz improvisation.” I note that a Wiki editor has added a “[citation needed]” tag next to that statement, and indeed, it needs one. A Day in the Life – the album – is loaded with improvised sections. Gunther Schuller, through a secondary source, says that “[Wes Montgomery’s] playing at its peak becomes unbearably exciting, to the point where one feels unable to muster sufficient physical endurance to outlast it.” Indeed, you hear some of that on “California Nights” on this album – the high-flying, breathtaking Wes Montgomery solo where he goes and goes and you think it will never stop. It’s just not as long a jam as the one on “Bumpin’,” but it’s there. What put Wes Montgomery into the malls was not his alleged compromise to the Mammon of commerce but A&M’s savvy marketing strategies. They were getting their music around everywhere. After my parents broke up, my mom briefly dated a man named Mike, whom I thought was an ass. But he had a splendid 8-track system in his car, and as he was too cheap to buy an 8-track to listen to, always played the one that came with the machine, an A&M sampler. It had several Wes Montgomery tracks on it, and I was always glad to hear them; “I Say a Little Prayer” sounded great in that car.

Some have pointed to Wes Montgomery as a pioneer of “smooth jazz.” I like me some smooth, and I greatly respect some of those players, but if I hadn’t read this inference the thought would never have occurred to me. I think we are confusing smooth with what was once called ‘Easy Listening,’ a term banished from the vocabulary in some quarters but nonetheless one that has some relevance in regard to Wes Montgomery. His later albums did figure in those playlists, on those radio stations and it’s another reason why his music made it into the malls. Wes’ approach was a softer touch on those 60s hits than the originals, and there was a market for that: my mother once complained that she had a co-worker at the University of Cincinnati who told her that when The Beatles did their own songs it was evil music, but when 101 Strings and the groups he liked did the same songs it was “okay.” Some folks had such convictions on religious grounds as well; rock music was “garbage can music” but the songs by themselves were not so bad.

The copy of A Day in the Life I found in Northside is a later pressing with the gray and olive label used from 1973 to 1988; its inner sleeve has releases from 1973 on it. The vinyl during this period was a little better than what had been used by A&M in 1967. My first copy, found in a thrift store in San Jose in 1979, I had to leave behind when I left suddenly on my 18th birthday. It was fairly battered, and I found a better one in a record store I used to frequent in Santa Monica in the 90s, but lost that with the storage locker, so I am glad to have this one. It is far from being a rare album, and is easy to find; Montgomery’s two other A&Ms are a bit more scarce, but not terribly so. Best to have any of them on vinyl, as practically all A&M CDs are shoddily prepared and have wretched sound; Alpert and Moss sold the company to the future UMG just as digital came in, and had little control or say as to the quality of CDs before being edged out of the company in 1993.

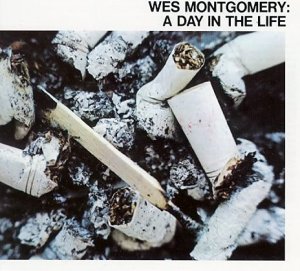

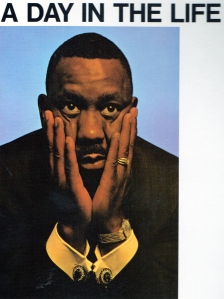

Filmmaker Jud Yalkut introduced me, about 1980, to the Sakurazawa Nyoiti book You Are All Sanpaku which describes the condition of whites of the eye visible below the pupil as a sign of illness and fatalism. As I read, my mind turned to the picture of Wes Montgomery on the back of “A Day in the Life” with its grim, unsmiling portrait of the guitarist, clearly sanpaku, if you believe in that sort of thing; perhaps Wes could’ve used a little of Don Cherry’s “Brown Rice.” Flip the album over and you are greeted with a huge, close up shot of spent cigarettes which is hardly the most attractive cover image one could imagine; how many of us spend our time staring into ashtrays? And of course, Wes Montgomery only outlived the October 1967 release of A Day in the Life by about eight months, dying suddenly of a heart attack in Indianapolis on June 15, 1968. At the time it made me wonder if, indeed, Wes was dogged by the fatalistic demon that Nyoiti described, but now, I think not. I suspect the album design was in keeping with the project, that Wes Montgomery had something serious to say about then-current popular music, wondrous and different from old standards like “Willow Weep for Me” which he’d always played. It seemed to me then, and seems more so now, that his intentions were completely sincere.

Just as we no longer think of The Monkees as “the Pre-fab four,” I think we ought to discard notions like this – I think it’s old, pre-edited Yanow – shown on All About Jazz, “By the time Montgomery released his first album for A&M Records, he had seemingly totally abandoned the straightforward jazz of his earlier career for the more lucrative pop market.” I think Pat Metheny, writing on his own site, is more on the money: “Wes was a carrier of the flame residing in each major player that has illuminated the essential jazz tradition. He was an embodiment of the forward-thinking improvising musician, who looked with wisdom and curiosity into the heart of his own moment in time, and played a music that commented upon the nature of that cultural moment through the prism that the sophistication of the form at its highest level mandates.” Amen, brother.

David “Uncle Dave” Lewis Hamilton, Ohio 11-24-2014